The hamlet of Tesselaarsdal is in the Overberg, about midway between Caledon and Stanford. It’s 135km from Cape Town and after tracking the N2, can be reached via a network of country roads through sprawling farmlands. The wine company named after the settlement is owned by Berene Sauls who was raised there, and its wines are made in the Hemel en Aarde Valley winery of Hamilton Russell. The grapes are from Hemel en Aarde too.

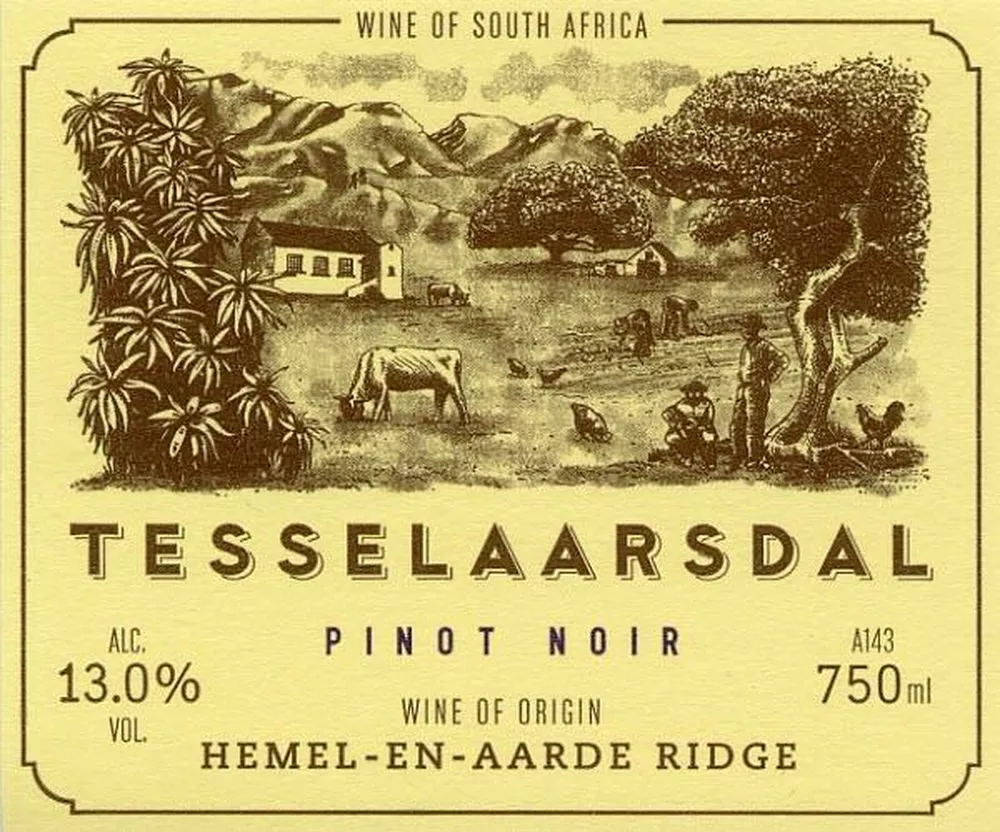

When we first meet, it’s beside the pioneering winery’s tasting room. She has a bottle and conversation immediately turns to the label: an alluring pastoral sketch, with a chicken and cow and other such detail.

“If you travel from Caledon to Tesselaarsdal, you cross over a hill and see this mountain range,” Berene says, tracing the lines as she has done a multitude of times in recent years. “I took a photograph of it for the drawing. The aloes grew along a fence near the post office, but they’ve since been cut down.

“There’s the Anglican church, the town’s first. The oak tree is near my mother’s house. This other tree is on the Groenewald’s farm; they’ve been there forever. And that’s the store on their farm. The chickens are there and the scrawny cow too.”

A young Cape Town designer, Simone Hodgkiss, drew the sketch for the label. She also designed the crest sporting a knight’s helm atop a shield with trio of Blue Cranes.

Back to the label, there are two figures on a path – the so-called Barber’s Trail. “The path leads to Stanford and is part of a mountain bike trail today. When I was younger, my mother and grandmother walked it once a week with their goats. They’d trade the goats for oil, fruit, sugar and flour.

“My mother always says it took them an hour to market, but two and a half hours back because of my grandmother’s drinking. They’d have to stop at the big flat rock halfway along to sober up before getting home,” Berene says with a chuckle.

She leads me through the maturation cellar to a table set for a tasting. I ask how she came to be here, in the limelight with her own wine label.

“I’m from a family of women with strong personalities,” says Berene, who has an easy smile and equally ready sense of humour. “And Ouma Dot had a strong brew of her own.” Ouma Dot turns out to be Rebecca Swarts, the village midwife. She adds: “Everyone basically had the same name. My mother was Rerena; there was also Marena, et cetera. Some later changed their names.

“When she turned 16, my mother took a loan to study and become a teacher. Her mother wanted her to join her in the kitchen where she worked part-time, but my mother refused. She was the first kleurling in Tesselaarsdal with a driver’s licence; she built her own house. They were my inspiration.

“As schoolchildren, the only jobs we aspired to were those with uniforms,” she says. “My upbringing was quite formal and militaristic.”

“I wanted to become a combat officer, but I eventually failed the aptitude test. Thank goodness!”

In February 2001 she took a job as au pair in the home of Anthony and Olive Hamilton Russell, owners of the eponymous Hemel en Aarde Valley wine farm. A month later she moved on.

“’You’re bright,’ Anthony told me. ‘Go help in marketing,” Berene recalls.

Soon after, a question started to form that would eventually be a turning point in her life. “We never paid more than a R5 or R10 for a beverage. I wanted to know why people were prepared to pay as much for wine as I saw them paying for Hamilton Russell.”

Anthony suggested another move; this time, to the cellar. “’Go talk to the vineyard manager and winemaker’, who was Kevin Grant at the time, ‘and see what they do,’ he told me.”

It was March by then and harvest was finished so Berene helped Kevin drawing samples and assisting with certification. “I also started operating the forklift.”

She later helped out with labelling and packaging, where she headed a team of six. At the same time, she embarked on courses through the Cape Wine Academy. “When they had tastings, I’d drive through to Stellenbosch after work. The next day, Anthony would ask what we’d tasted and what I thought.

“It took two years before I was confident in my senses,” she says. “[Growing up] we were exposed to many things, but some of the fruit they spoke about at the wine tastings were unknown to me. I would often go to the shops to find out what they were talking about.”

Berene found herself working in the tasting room on occasions and in logistics too. Here, the response to her questions about how to fill out the forms was met with a suggestion she phone the applicable government department. “That was the deep end and I truly underwent a metamorphosis.”

She also managed to graduate with a qualification in business management and export logistics through UNISA.

Then, in 2014 Anthony approached her with an idea – why not try making your own wine? By this time, Emul Ross had been appointed as winemaker and he would advise her. Hamilton Russell would give a small financial leg-up, but she would have to register a business and source her own grapes.

“I could use one of the farm buildings for my liquor license,” she says.

“With Emul’s help, I started looking, but grapes here are rare because of their quality. Everyone wants some. All I knew at the time was [Hamilton Russell stalwarts] Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. We eventually found a block of Pinot noir.

“Emul and I had two students to help with harvest and we retrieved just over a ton of grapes. It was a good harvest [2015]. We produced 1 202 bottles and used whole bunches. I learnt a lot and the process itself was very personal.

The marketing of that first wine happened through opportunities again realised by Hamilton Russell. “At every show I kept a bottle under the table and would pour it for potential customers. I would note down names in a notebook I kept and eventually, almost the entire consignment was pre-sold.

With the Pinot Noir Celebration of the following year, visitors arrived on the farm in droves. Again, Berene kept a bottle ready for impromptu tastings. “Anthony told me just to keep writing names and talk as much as I can. [In Afrikaans, she describes his advice to “praat jou alie af”]

“One visitor took a photograph of me with the bottle and later that afternoon the messages started coming in. People from all over wanted wine.”

It turned out the photographer was UK-based Master of Wine Greg Sherwood, and he’d shared her picture on his social media networks. “Anthony cautioned me: ‘It’s your business, but don’t put all your eggs in one basket,’ he said.”

That evening she began sorting through the orders for export to the UK and US. “The rest was sold instantly here in the Cape.”

Berene lists the buyers off the top of her head: 63 private individuals as well as restaurants including La Colombe, Test Kitchen and Pot Luck Club and Overture. “Dit was crazy!” she exclaims.

Next, she made allocations for the following harvest – some 200 cases. Berene says she kept just 30 bottles of the 2015, “of which there are now just 29,” she adds with a pause having poured for our tasting.

The price of her wine escalated over the years, starting at R350/bottle and migrating to R525/bottle for the current vintage.

I return to her early question about what goes into the price of wine. “I can answer that with confidence,” she beams. “If you want good quality grapes, you’re going to pay for them.”

That lesson continues to play out as the cost of grapes continues to climb and her commitments increasing apace. She recently acquired 16.6ha of virgin land on the road to satisfying a dream. “We need to plant vineyards, establish infrastructure, do soil mapping, sink boreholes. It adds up quickly and it’s a lot of money,” says Berene.

She has been able to access funding from government and industry bodies that have support programmes for emerging farmers. She has also ploughed in prize money from several competitions she won.

She still works full time at Hamilton Russell and has to fit in her own business after hours or take leave.

She recounts the experience of raising money. “I don’t have assets, and even the car I drive isn’t mine so I couldn’t get a loan for the farm.” She vocalises an imaginary conversation with a bank clerk: “You want how much?!” and then leans back with her hands on her belly with mock-chuckle.

She’s been on the hunt for land for some time. A few deals collapsed. Emul has been by her side to help. With the latest site, he was confident it would make a good starting point.

“I took my two sons to see the land and told them: this, is our farm.” Berene Sauls

Her sons are aged 16 and 9. Her next step was contracting a geohydrologist to advise on water – he identified three potential locations.

But the novel Corona virus put the brakes on many of her plans. Her production has steadily increased since launch. This year, she doubled production of the 2020 Chardonnay. At R250/bottle and the cheaper of her two offerings, she hoped it would help fuel her investments. Instead, the business was saddled with extra weight. “I would have gone to ProWein and then WineX in Sandton,” she says. “I’m trying to get everywhere in South Africa.”

She was hoping to plant her first vineyard next year. Water for the partial irrigation still must be found.

She’s hoping to eventually put up a 30-ton capacity cellar with a tasting room. A five-hectare portion of the property is Renosterbos and she wants to retain that for conservation.

“If things go well, that cellar will be built in year five. We want to plant Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, but we’re still planning. Covid has forced me to re-look at my production numbers.”

While most of her stock traditionally went to the US, UK and Norway, Berene has had to start selling online and grow local distribution points too. “I’ve let customers know about my purchase of a farm and they’re very excited about the developments.”

If plantings proceed according to plan, she wants to harvest grapes in seven years. “But, it was the wrong year to increase production. My local sales are down and two markets crashed.”

Nonetheless, attention on Tesselaarsdal Wines and Berene emerged from an unexpected, but influential source – the Black Lives Matter movement. With protests gaining pace in the US following the death of George Floyd, Berene saw increasing requests for interviews from that country as well as Denmark. “People sought me out. The result has been that despite having lost two markets for my wines I’ve gained three others. People said they saw me in the Wine Advocate, too.”

At the time of writing, Berene’s Chardonnay was being bottled. Things may have hit a bump for Tesselaarsdal. Its owner may be re-calculating, but she’s certainly showing no sign of slowing down.